Opening the Way of Wu: A Manifesto

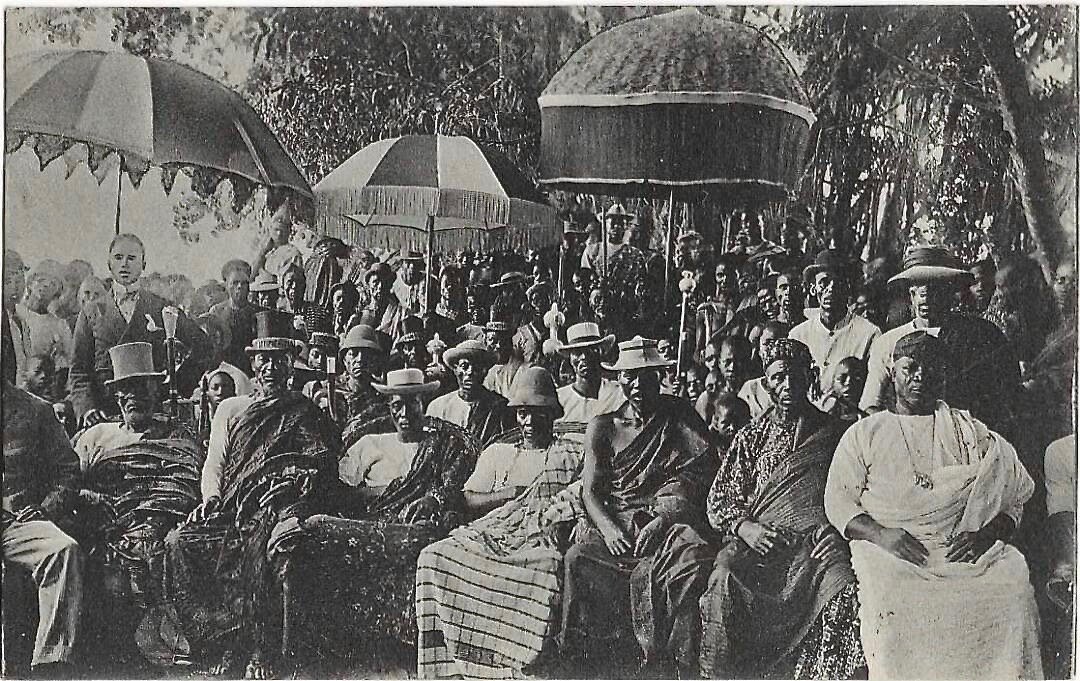

The man wearing a black top hat and sitting a head taller than everyone else in the photograph above is my great, great grandfather, Torgbui Dukli Attipoe I. The word 'torgbui' in Ewe means chief and that’s what he was. Attipoe is my family name on my mother's side. I don’t know exactly when the photo was taken but if I project back a reasonable amount and piecing together some family history, I reckon the photo was taken sometime in the late 1800s.

Eka xoxoawo nue wogbea yeyeawo ɖo = it is onto old ropes that the new are woven

I am an Anlo-Ewe from Ghana, a sub-group of the Ewe people who live in Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria. While I understand the Ewe language very well on the ear, my peripatetic upbringing, first in London and then in several West African countries, means that I was never immersed in it for long enough to become a fluent speaker of it before I returned to the UK when I was seventeen. This can be very discombobulating especially when I’m so used to being very articulate in English. It feels like an existential yawning in my soul when the yen to reflect my Anlo-Ewe heritage in my work feels so urgently primal. So it threatened to shake my soul loose from its moorings, while doing some research, when I read that not being fluent in the language, as part of a collective Ewe destiny, is tantamount to self-excommunication in Anlo-Ewe philosophy.

Some years before that, I’d started to pick my way into connecting my Anlo-Ewe heritage to my writing in English through the figure of Legba, the trickster god in Vodun. He is the gatekeeper, guardian of the crossroads and opener of the way. In Vodun cosmology, his phallus is said to be the bridge that connects opposites - day to night, human to divine, heaven to earth etc. Crucially for me, he also rules language, communication and drumming which, as a writer, feels very fitting. That’s why I’ve put his sigil at the top of every page on this website, to invoke his gift of the gab and to open the way for this writing life. More recently, I decided that a workaround for not being fluent in the Ewe language is to soak up as much of the history, philosophy, cosmology and migratory stories of Anlo-Ewe people as research and what I could glean from talking to older members of my family would allow.

But I also read in my research that before Western-style documentation started, Anlo-Ewes historically stored their experiences in the ritual of dance to pass down the generations. This steadied me. The many forms of Ewe dance is a language my body knows how to speak because I had done a lot of it when I was in school in Ghana. The research also gave me an inkling of how I might approach poetry writing, theatre making and other art making, in a holistic way that honours all the parts of my being. I found this in the concept of Wu.

According to Anlo-Ewe philosophy, four elements constitute life. They are: Gbe (sound), Ga (rhythm), Dzo (vibration) and Dza (movement) all of which form a holistic art form, known as Wu (dance or dance-drumming) often regarded as one of the most impressive tools for effective communication. It centres tseka, the spinal cord, through which the brain sends dzo, vibration ie. energy (the same word also means fire or light) to the other parts of the body. Wu informs gesture, movement, rituals, social interaction, songs, stories, festivals, religious and political ceremonies, philosophical concepts, names and dialogue. In short, it informs just about everything a body can experience.

As an Anlo-Ewe proverb indicates, Wu is ‘the back without which there is no front.’ In other words, to go forward I have to look backward. It’s a philosophy that’s become a foundation upon which I can exhibit a shared connection to all Ewe peoples while still pursuing my own individual artistic preoccupations.

Wu is ‘the back without which there is no front.’

Part of looking back to the past to inform the present in dialogue with the future is rooted in family, namely ancestry. That is "the back without which there is no front.” Which brings me back to the photograph above. Torgbui Duklui Attipoe I was a renowned traditional ruler, hunter and warlord who fought many wars including one to abolish the Slave Trade. Such was his bravery that the British named him ‘War Captain’. For his exploits and leadership, Torgbui Attipoe was presented with a globe and that top hat by Queen Victoria. Apart from his huge cotton farms at Keta and Anyako, he was also a merchant, who used his vast knowledge of herbs to produce very attractive colours used as dyes for his batik business. He died in 1903, leaving behind 11 wives and many children. So much to dig into these scant details about his life. That is a gift to me as a writer.

When I first used to perform on stage, around the same time I was channeling Legba in my work, I'd always wear a black top hat. That was before I knew about Torgbui and this photograph but maybe, somehow, I got the inclination from him? I've still got the top hat but it doesn't come out as often these days but maybe it's time to dust it off to channel Torgbui? To channel Wu? As the elders say: "How can you know where you are going when you do not know where you are coming from?"

As much as I love this photograph, the women not in it are conspicuous by their absence in front of the camera. Wu has implications for how I think about myself, my womanhood, my creativity and what it means to be a Ghanaian-British poet, artist and writer. By centring Wu in my poetry, in my work, I have a tool with which I can engage a decolonisation of the mind, giving empowerment and agency to this black female body through a deep-rooted enquiry into ancestry. It is onto those old ropes of family that new ones of connection and belonging are woven. Wu is also a means to counter the imperial legacy of the English language even while I push at its boundaries to establish an organic relationship between Ewe oral tradition of which poetry is a very important mode of discourse and poetry written in English. In Anlo-Ewe cultural understanding, a drum is a super projection of the human voice. This makes Wu, in its definition as dance-drumming, an integral part of this writing life. Wu + the instinct to tell stories through writing is drum language.

Dzongbe ga yenye akorsu = vibration of sound, rhythm and motion constitutes the birth and control of life

When I think of myself dancing to drum language in Wu, I channel the eloquent braggadocio of Legba. As an unexpected delight, Wu is also bringing me closer to the Ewe language because I’m beginning to understand a lot of the conceptual origins of its mechanics by invoking Wu.